Contained in the Proemio to Cristoforo Landino’s Comento on the Divine Comedy is a chapter that comprises the full text of one of Marsilio Ficino’s Latin letters and in which he presents Dante’s coronation with laurel. The scene is surely one suggested by Dante himself when he prophesies his return to the Baptistry to be crowned as poet laureate: ‘con altro vello | ritornerò poeta, e in sul fonte | del mio battesmo prendero ‘l capello’, Par. 25. 7-9. This coronation is brought about through the agency of the poet, vates Landino himself, and the text reads:

‘recently your [sc. Dante’s] father Apollo, made pitiful from my long weeping and your eternal exile, sent Mercury to enter the devout mind of the divine poet Cristoforo Landino. Having assumed Landino’s appearance, he used his wand to awake your sleeping soul, his wings to take you inside the walls of Florence, and finally he crowned your temples with Apollo’s laurel’, ‘nuper tuus pater Apollo, et longum flectum meum, et diuturnum tuum exilium miseratus, mandavit Mercurio, ut pie Christophori Landini divini vatis menti prorsus illaberetur; Landineosque vultus indutus, alma primum virga dormientem et suscitaret, deinde alarum remigio te sublatum menibus Florentinis inferret; denique Phebea tibi lauro tempora redimeret’ (Comento, Procaccioli ed., I, 268, 6-11; trans. Gilson, p. 191). I cite this passage from Simon Gilson’s new book on the Renaissance rezeption of Dante because it is a rather densely-textured attempt to reintegrate Dante as auctor in Florence’s cultural history. Landino as commentator becomes an auctor, and is divinely inspired just like Dante. The Comento is trading in the authority of Virgil’s Aeneid with Mercury’s remigio alarum (cf. ‘de’ remi facemmo ali al folle volo’, Inf. 26. 125), but he is also doing so through the voice of Marsilio Ficino, another of Florence’s vates. The commentary impulse is nicely revealed here, where the commentator seeks to establish his own auctoritas through the excerpted voices of other auctoritates, ventriloquising, imitating and emulating. And now the commentator himself must be up to the job of praising the great poet and needs inspiration, not just ingegno. The Commentary becomes another work of poesia in a way, written by a Poeta.

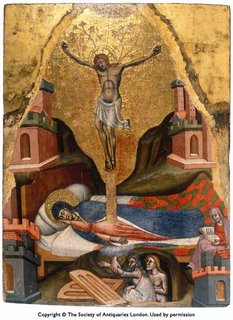

The illustration, which also forms the dustjacket to Gilson’s book, shows Dante crowned with laurel outside the city walls of Florence, with the city in the background beside the mountain of Purgatory. (Does that mean that Florence is Hell?) It’s by Domenico di Michelino and is a tempera on panel in the Duomo in Florence, and dates from 1465 (232.5 x 292 cm). Dante holds a book, his Comedía, from which rays of light shine forth. It’s almost a holy book. So Dante stands with one of Florence’s great literary treasures, the Comedy in front of Brunelleschi’s Duomo, one of Florence’s great architectural treasures. The Landino/Ficino quotation above shows how important it is to repatriate Dante (and there’s much discussion in the Renaissance about bringing Dante’s bones back to the city) by having him re-enter the city, a kind of obsessive complex over his forced exile caused by the city itself.

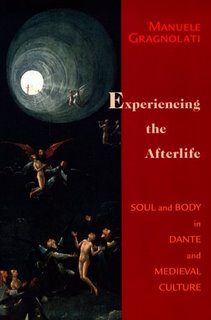

Gilson’s book is in three parts. The first, entitled ‘Competing cults: the legacy of the Trecento and the impact of humanism, 1350-1430’, pp. 21-93, treats mainly of Boccaccio and Petrarch and the dichotomy of Dante reception between these two poets. Boccaccio is the great admirer, copier, compiler of Dante’s work, and his own writings are hugely influenced by Dante. Petrarch is notoriously cool towards Dante and is often characterized as unimpressed with Dante’s so-called ‘humanist’ credentials. The rest of the book, then, is broadly about how this dichotomy of denigrating Dante or glorifying him runs throughout the Renaissance and its reception of the Poeta. The second part, entitled ‘New directions and the rise of the vernacular, 1430-1481 (pp. 97-160), looks at Dante as a civic and linguistic model, and at critical judgments of Dante’s poem. The third part is about Cristoforo Landino’s Comento sopra la Comedia, which dates from 1481. Much material, all of it fascinating, it certainly is required reading for any bibliography on ‘The Afterlife of Dante’. My only criticism is that such is the spread of material there was not more time to work out the implications of the positions humanists were taking in respect of Dante. Often Gilson identifies loci of Dante resonances in humanist texts but does not proceed to ask why those localized occurrances might be interesting or significant. It’s not a serious criticism really because now the material has been put together. But I was often left wanting more. It is extremely well documented with a wonderful bibliography. Cambridge University Press’s usual high stardards of finishing the book have left little to correct for the paperback.

‘recently your [sc. Dante’s] father Apollo, made pitiful from my long weeping and your eternal exile, sent Mercury to enter the devout mind of the divine poet Cristoforo Landino. Having assumed Landino’s appearance, he used his wand to awake your sleeping soul, his wings to take you inside the walls of Florence, and finally he crowned your temples with Apollo’s laurel’, ‘nuper tuus pater Apollo, et longum flectum meum, et diuturnum tuum exilium miseratus, mandavit Mercurio, ut pie Christophori Landini divini vatis menti prorsus illaberetur; Landineosque vultus indutus, alma primum virga dormientem et suscitaret, deinde alarum remigio te sublatum menibus Florentinis inferret; denique Phebea tibi lauro tempora redimeret’ (Comento, Procaccioli ed., I, 268, 6-11; trans. Gilson, p. 191). I cite this passage from Simon Gilson’s new book on the Renaissance rezeption of Dante because it is a rather densely-textured attempt to reintegrate Dante as auctor in Florence’s cultural history. Landino as commentator becomes an auctor, and is divinely inspired just like Dante. The Comento is trading in the authority of Virgil’s Aeneid with Mercury’s remigio alarum (cf. ‘de’ remi facemmo ali al folle volo’, Inf. 26. 125), but he is also doing so through the voice of Marsilio Ficino, another of Florence’s vates. The commentary impulse is nicely revealed here, where the commentator seeks to establish his own auctoritas through the excerpted voices of other auctoritates, ventriloquising, imitating and emulating. And now the commentator himself must be up to the job of praising the great poet and needs inspiration, not just ingegno. The Commentary becomes another work of poesia in a way, written by a Poeta.

The illustration, which also forms the dustjacket to Gilson’s book, shows Dante crowned with laurel outside the city walls of Florence, with the city in the background beside the mountain of Purgatory. (Does that mean that Florence is Hell?) It’s by Domenico di Michelino and is a tempera on panel in the Duomo in Florence, and dates from 1465 (232.5 x 292 cm). Dante holds a book, his Comedía, from which rays of light shine forth. It’s almost a holy book. So Dante stands with one of Florence’s great literary treasures, the Comedy in front of Brunelleschi’s Duomo, one of Florence’s great architectural treasures. The Landino/Ficino quotation above shows how important it is to repatriate Dante (and there’s much discussion in the Renaissance about bringing Dante’s bones back to the city) by having him re-enter the city, a kind of obsessive complex over his forced exile caused by the city itself.

Gilson’s book is in three parts. The first, entitled ‘Competing cults: the legacy of the Trecento and the impact of humanism, 1350-1430’, pp. 21-93, treats mainly of Boccaccio and Petrarch and the dichotomy of Dante reception between these two poets. Boccaccio is the great admirer, copier, compiler of Dante’s work, and his own writings are hugely influenced by Dante. Petrarch is notoriously cool towards Dante and is often characterized as unimpressed with Dante’s so-called ‘humanist’ credentials. The rest of the book, then, is broadly about how this dichotomy of denigrating Dante or glorifying him runs throughout the Renaissance and its reception of the Poeta. The second part, entitled ‘New directions and the rise of the vernacular, 1430-1481 (pp. 97-160), looks at Dante as a civic and linguistic model, and at critical judgments of Dante’s poem. The third part is about Cristoforo Landino’s Comento sopra la Comedia, which dates from 1481. Much material, all of it fascinating, it certainly is required reading for any bibliography on ‘The Afterlife of Dante’. My only criticism is that such is the spread of material there was not more time to work out the implications of the positions humanists were taking in respect of Dante. Often Gilson identifies loci of Dante resonances in humanist texts but does not proceed to ask why those localized occurrances might be interesting or significant. It’s not a serious criticism really because now the material has been put together. But I was often left wanting more. It is extremely well documented with a wonderful bibliography. Cambridge University Press’s usual high stardards of finishing the book have left little to correct for the paperback.