Bernard O’Donoghue (born in Cullen, Co. Cork, 1945) has just published his fifth collection of poetry Farmers Cross (sixth if you count his Selected Poems by Faber in 2008) and it is a work of beauty, of sadness, of delicate memories polished by continual, countless recollection. Much of O’Donoghue’s poetic voice is poised between the Ireland of his childhood and the England of the greater part of his life, his education and his career as a fellow in Oxford, where he teaches medieval literature as well as twentieth-century poetry. This inbetweenness makes for a powerfully observed poetic of belonging and non-belonging, of the outsider and the local, with an eye for detail that no local could see but to which no outsider would have access.

The collection’s title poem, ‘Farmers Cross’, explores events immediately following the death of his father and his mother’s decision to return to England. A cheque signed on the day he died, paying for his subscription to the

Irish Farmers Journal, was returned marked ‘Not honoured: signatory deceased’. While his mother ‘took to farming like a native’, his father ‘hated farming: every uphill step | on the black hill where he’d been born and bred.’ Farming for him was a cross, unwillingly inherited. She was good at it, despite her city upbringing (‘as if she’d not grown up by city light’), and has a strong sense of the honour, dignity, and sacrifice of the work. Its rewards, for her, are reaped in the next life: ‘she always said the front row in Heaven | would be filled exclusively by farmers’. But no matter how good she was at farming, no matter how much of a native she resembled, she had married into it, and when her husband died, her connection with the farm was lost. The townland of Farmers Cross is where the airport in Cork was built, on a hill and prone to fog. It is from here that his mother leaves for good, as ‘the lights | fought a losing battle with the fog’. Its atavic identity as a

farm persists over its subsequent use as an airport: ‘they’d | always said it was a hard farm to work’. Farmers Cross, then, becomes the point of departure as well as the point of return for the poet, both in his imaginative and real geography.

The ground worked in

Farmers Cross is not just that in the Cork of O’Donoghue’s childhood but that which he came to work himself over the years: the poetry of the middle ages. There is a translation of

Piers Plowman (B

Prologue 1—37), a man who knew the land, a poem all about getting into that front row in Heaven. There is a translation of Dante’s

Purgatorio 2. 61—81, Virgil and Casella, which opens: ‘«Voi credete | forse che siamo esperti d’esto loco; | ma noi siam peregrin come voi siete’, rendered as: ‘I think you must believe | that we know all about arrangements here; but we are outsiders, just the same as you are.’ That

esperti d’esto loco (echoing of course

Inferno 26. 98 and the ‘expertise’ of another great traveller, Ulysses) becomes a very vernacular ‘arrangements’, while

peregrin moves from ‘pilgrim’ and ‘stranger’ to the somewhat starker ‘outsider’, echoing a theme very much being explored in

Farmers Cross. The theme of the traveller, the outsider, is not explored via the figure of (Dante’s) Ulysses but instead an older, and altogether

stranger figure in the Old English poem ‘The Wanderer’. O’Donoghue effortlessly allows the poem’s universality to compellingly apply itself to the present (pp. 28—9):

Cities lie in ruins; populations lie dead,

their bodies heaped by the crumbling walls.

Some die in battle, but more are victims

of assaults from the skies. Some are left

for scavengers to come under cover of night

to steal what they can. Few have the honour

of dignified burial by friend or relation.

Compare the Old English:

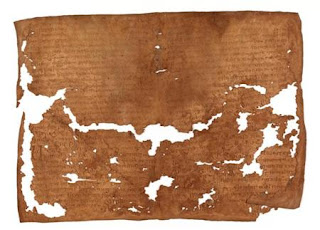

Wōriað þā wīnsalo,———walden licgað

drēame bidrorene,———duguþ eal gecrong,

wlonc bī wealle.———Sume wīg fornōm,

ferede in forðwege,———sumne fugel oþbær

ofer hēanne holm,———sumne se hāra wulf

dēaðe gedǣlde,———sumne drēorighlēor

in eorðscræfe———eorl gehȳdde.

Bruce Mitchell, the great Old English scholar, described the Wanderer’s philosophizing as ‘strong in feeling, high in dignity, and wisely reflective’: I can think of no better description of Bernard O’Donoghue’s

Farmers Cross.